If you’re queer, there’s no doubt some part of Kelsey Wroten’s debut graphic novella Crimes that will strike a blow to your heart. The back cover blurb of Crimes bills it as a book that “confronts selfish desire, intimacy, loss, and the unconventional ways in which we try to find connection in others”. The “unconventional” connection around which the narrative orbits is narrator Willa’s inexorable crush on her friend Simon’s girlfriend, the young, enigmatic and straightforward poet Bas, but all of this is filtered through the specter of death with which the book opens, foregrounding its examination of existential and romantic uncertainty that is complicated by an internalized condemnation of the self.

Wroten opens Crimes with a flashback to a conversation between Willa and her father, in which they discuss belief in God. Willa, a budding atheist, believes there is no logical sense to faith; there’s no proof that God exists. Her father presents an alternative view, which, unacknowledged by him, is Pascal’s wager; the believer stands to lose a measurable amount of material and pleasure in life by following religious tenets, whilst gaining resplendent eternity, whereas the atheist stands to gain only oblivion if she is right, and hell if she is wrong.

This conversation sets the stage for Willa’s uncertainty about her place in the world, one built upon a foundation of spirituality which condemns her and all mankind as inherently sinful. Interestingly enough, it also presents faith and skepticism not as an opposition between wishful hope and reason, but as two diametrically opposed mathematical equations, each with the same unknown variables.

This maybe/maybe-not of faith serves as an intriguing parallel to Willa’s crush on Bas which exists in the space of queer uncertainty over whom can even be considered a potential romantic partner. When Bas finds out Willa is gay, she immediately asks “How do you know when “stuff” between women is over? With men it’s pretty obvious…” - foreshadowing Willa and Bas’s later falling out over Simon’s untimely death - Willa admits it is more difficult “knowing when something begins” when you’re queer. “When there’s a chance something might happen at first, possibilities are obfuscated by both desire and conjecture, then you wait for it to tip. For the crucial exchange of mutual interest. Sometimes it never happens, even when the pieces are all there,” she says. In a heteronormative culture, romantic possibility hovers over almost any two adults on opposite ends of the gender binary, which is not the case with other interpersonal dynamics. “I find it hard to deal with developing feelings in general because there’s a huge question of ‘Is it even possible she could be into me too? With straight people there is so much ground that is covered for you. Any energy can be read as romantic by default, even when it isn’t.”

Elsewhere, Wroten interrogates how duality characterized by ambivalence and contradiction play into uncertainty as endemic to the human condition, invoking Simon’s fascination with herpetology. Wroten’s mastery of visual language emerges beautifully here as a cinematic match cut between panels transitions from one inky frame of Willa’s crossed paint strokes to a second panel of a two-headed snake. As a metaphor that calls to mind both original sin and warring halves of the divided self, Willa narrates Simon’s description of axial bifurcation in snakes, a condition in which the ordinarily solitary milk snake is born with two heads, each one believing itself to be the “true” snake. In the end, Simon tells Willa, one snake will likely cannibalize the other as the two heads will hardly ever be able to agree – subsequently killing both of them.

Willa’s powerful attraction to Bas undergoes just such a constant and agonizing tug-of-war, as she can neither seem to initiate anything with Bas nor deny the force of her infatuation over the course of their many encounters, during which they discuss art, sex, and how both are implicated in identity. In many ways, they contrast one another.

Bas’s romantic and physical gravity draws Willa in even as she resists the pull, conflicted over Bas’s relationship with Simon, whom in addition to being Willa’s friend, is also a widower. Willa and Bas’ inevitable intimacy at the book’s climax is punctuated by the news of Simon’s death, which seems almost punitive, like a divine judgment. Like Simon, who lost his first wife, and Willa, who is, as Bas indelicately puts it early in the book, “an orphan” (“it’ll happen to you too, eventually,” Willa retorts), Bas, too, now experiences the cruelty of a death in close emotional proximity. Death, as Willa describes it in the opening (post-Simon’s death) is “perfect dark”, the interior of an ever-present coffin – and she wakes up sometimes in the dark feeling like she’s already underground. As Willa tries to watch a relaxing video and take part in a visualization exercise where she imagines a place of “safety...love,” images of childhood hide-and-seek are quickly supplanted by a flashback to her romantic interlude with Bas. No sooner does she envision Bas’s face, than the doorbell rings, delivering a posthumous package from Simon, like a rebuke from the afterlife.

Wroten’s visuals in this book appear to depart from her more recently full-length graphic novel Cannonball which came out last month and sold out its first run. Cannonball is colorful, more conventionally stylized, and neater than Crimes, which has a rough, inky feel to its black-and-white pages. In both works, Wroten’s writing really shines through her dialogue, which is funny, dark and organic. She has a knack for writing conversations that humanize her characters even as they self-deprecate or make awkward attempts at witticism.

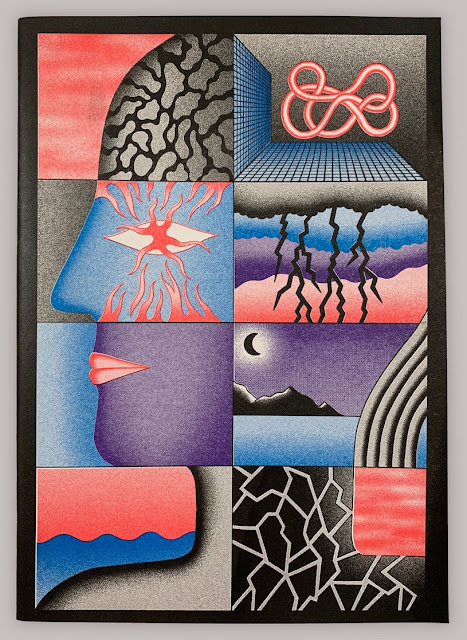

Wroten’s exploration of uncertainty and existential confrontation through expressive art takes on an interesting dimension as a graphic narrative that involves two characters making, individually, work that is visual (Willa) and textual (Bas). “The magic of poetry,” Bas pontificates after Willa sees her perform for the first time, “is in the arrangement of words in a new way…I believe in it. These days, there is a growing shame associated with hope and earnestness.” With Crimes, however, Wroten suggests that isn’t a shame-worthy sin to believe in something – only naïve. Bas, young and incapable of fully appreciating death, can put her faith in the redemptive power of words. Willa, on the other hands, paints. “I am inept at expression” she admits, trying to make a painting for Bas and the late Simon, and envying Bas her poetic facility with language. Like Wroten’s haunting cover illustration for Crimes, Willa’s painting embraces uncertainty as one of life’s few absolutes, and suggests that Willa’s inability to confront herself fully through artistic expression is the result of a self-image that precludes the possibility of redemption. Not just for Willa, but for all of us.

-------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Sara L. Jewell is a freelance writer, artist, comic creator, and educator based in New Jersey. You can find her at saraljewell.com or rambling on twitter @1_saraluna. All email inquiries can be sent to saraljewell@gmail.com