Eva Müller’s fabulous poltergeist of a book, In the Future, We are Dead, makes no such concessions. Featuring an ostensibly autobiographical character who is every bit as anxious about and obsessed with death as DeLillo’s protagonist, Müller’s collection of nine “stories” – linked in rumination and obsession but neither by chronological nor narrative logic – successfully walls itself off from her own actual death by housing the inevitable in a prison of syntax that ensures it will never arrive: though the title understands that we, all of us, are dead, we are only dead in the future.

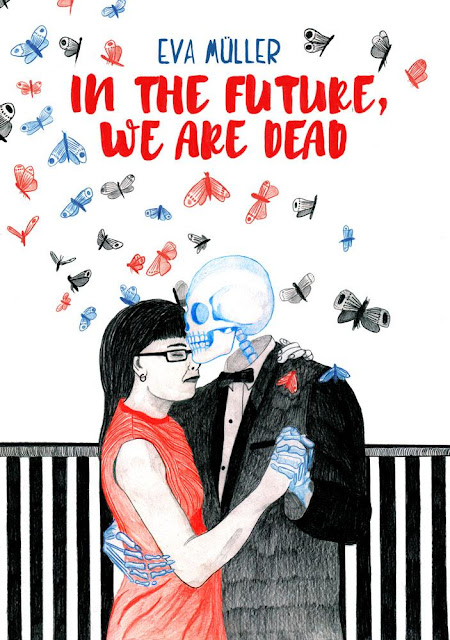

Like Gladney, Müller realizes that the real enemy facing someone obsessed with the finality of death is linear time; however, where Gladney is helpless to DeLillo’s authorial needs, Müller functions both as creator and character. Müller, creator of the artifact that is In the Future, We are Dead, kindly accommodates her own needs as a character by disrupting, suspending, and otherwise thwarting temporality in a number of ways that also subvert the sequential and generic logic typically central to the creation of a comic book. Part of this disruption has to do with a use of form and structure not dissimilar from White Noise; Müller creates nine distinct sections but only numbers four of them, rendering the notion of “chapter” as ineffectual or at least incomplete. Likewise, Müller creates vignettes that, like DeLillo’s first twenty chapters, resist readers’ attempts to create a single story. However, by alternating between “chapters” that are black and white and “chapters” that feature five carefully controlled colors, Müller takes advantages of an element unavailable to DeLillo to draw attention to cycles and patterns of repetition while managing to do what DeLillo could not, fending off plot completely.

In addition to the formally innovative efforts to free her own story from temporality, Müller employs two strategies to cater to her anxieties concerning the way that all stories must end. First, the episodes recorded in In the Future, We are Dead all feature dreams, visions, memories, and other meditations that, like the book’s title, suspend events and happenings in a present-tense where everything is now and nothing can change. Even if Müller evolves throughout her life in order to eventually accept ways in which she, every day, is living with death, she creates the book in such a way that death is free to simultaneously accompany her as an idea or fact while never arriving as a material reality; thanks to the literary present, she is in these pages, forever now, always already with death but never headed toward the future where she is dead. Death functions as an obsessive train of thought and an omnipresent subject of obsession; conversely and poignantly though, this strategy comes with its own tyranny. The present-tense benefits of embracing her anxiety in such a way that renders the future moot also traps Müller in episodes – her life in punk rock, her brief relationship with a woman who wouldn’t leave her house, and her complicated experiences with Yoga – that depict a life nearly devoid of a life story.

The perils and advantages of a carefully designed but, in turn, inescapable present-tense through which the past and future are both available only as ideas is most evident in the second mechanism through which Müller attempts to conquer time and sequentialism: the full-page panel. Again and again, Müller creates full-page layouts that look like early modern woodcuttings or paintings; unlike conventional full-page comic layouts, these pages do not feature complex or revelatory actions so much as they serve to fossilize moments as a-temporal religious iconography or text-book illustrations. Such pages resemble early Christian depictions of the Catholic saints and dare the reader to question the difference between accommodating one’s fear of death and living a life of self-martyrdom. The results are compelling, disturbing, sad, and resolute-if-not-triumphant in equal measure. As a reader who experiences his own anxiety disorder as a kind of solipsism, I found the book to be one of the most honest representations of the disability I have ever encountered: anxiety is a problem that presents itself as a tool to solve the real problem.

Returning to the color scheme, black and white sections – often associated with dissociation or depression – give way to and eventually reclaim sections that carefully introduce red, white, and blue. Though Müller wrote the book in German and it is never set in the United States, the book is hard to read, at least in her English translation, without thinking about the American flag. Thinking about existentialism as a genre and its premise that freedom is the real source of dread concerning life and its inevitable ending, the consistent and abstracted presence of these disembodied colors draw attention to the way that, both in creating the artifact of In the Future, We are Dead and in existing inside of it, every choice that Eva Müller makes is over-determined by her anxiety in order to resist the terror that is true freedom.

If it feels like a stretch to read Müller’s use of red, white, and blue – and only red, white, and blue – as a conscious attempt to associate anxiety with freedom as it is purportedly exported by America, it is worth noting that, in White Noise, DeLillo similarly correlates anxiety with invasive Americana. The opening section – featuring the twenty chapters most stylistically similar to In the Future, We are Dead is titled “Waves and Radiation.” In lieu of plot development, the reader gets extended litanies of product names and a series of musings about consumer detritus. In other words, anxiety is framed as a byproduct of late-stage capitalism that seeps into the natural world. While Müller may be doing something similar by featuring an American color scheme that threatens to encroach and overtake a black and white world, anxiety is depicted as much older post-modernity. For DeLillo, anxiety is generated, or at least heightened, by trends to understand capitalist consumption as a proxy for the pursuit of happiness. Müller, on the other hand, appears to understand anxiety as coterminous with the notion that happiness must or even can be pursued in the context of a finite lifespan. If DeLillo depicts anxiety as a man-made contagion produced by progress, Müeller sees it as a fundamental component of humanity endowed by a creator, the lack thereof, or even – if we take solipsism seriously – one’s own mind. What pollutes the world of White Noise creates and embodies the world of In the Future, We are Dead in which all objects, natural or otherwise, are haunted by an observer’s knowledge that nothing lasts forever.

Throughout In the Future, We are Dead, anxiety is simultaneously an infliction that inhibits living and a mechanism by which one copes with having to be alive and eventually die. Seeing death everywhere, every day, as Müller does, is a product of anxiety, but it is also a way to endow the physical world with its own ghost in the off-chance that spirits are not subject to the laws of nature.

Many books are haunted.

In the Future, We are Dead is haunted – stubbornly, completely – by design.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------------

Matt Vadnais has taught college literature and creative writing classes for twenty years. He is the author of All I Can Truly Deliver and a contributor at covermesongs.com. For more comics coverage and the occasional tweet about Shakespeare, follow him @DoctorFanboi. For short takes on longboxes, subscribe to his channel of video essays.

No comments:

Post a Comment