The editors of the New York Review Comics line have shown exceptional taste in their choices for reprinting obscure and untranslated comics. Some of their choices, like Dominique Goblet's Pretending Is Lying, are amongst the best comics I've ever read. Likewise, Marion Fayolle's The Tenderness of Stones is every bit as innovative and emotionally devastating as that work, only in a completely different way. In discussing her father's cancer (initially in remission) and his eventual decline and death, Fayolle unleashes a steady stream of lyrical, whimsical, and even absurd visual metaphors that blend into and stack atop each other. Like Goblet's work, this is a comic about coming to terms with a difficult relationship with one's father, only this comic carries a sense of time and circumstance preventing a true understanding. Even in his decline, Fayolle’s distant father is elusive, and the closeness she feels to him is illusory. At the same time, her family (mother, younger brother, and her) becomes a kind of actor's troupe in service to her father, creating a bond out of duty and performance.

From the very beginning, Fayolle's genius is in transforming medical realities into magical realist imagery. Her father had lung cancer and surgery to remove the diseased organ. The ubiquitous "men in white" had it taken out and told him to bury it. Thus began one of many instances in which she insisted her father was somehow trying to pull a prank on his family, that burying his lung was his way of seeing who would show up to his funeral. Fayolle later claimed that her dad was behaving like a child so he could be taken care of like one; acted as though he were a king in order to receive royal treatment; and was only pretending to be ill as he secretly went pub crawling at night. While these instances of magical thinking were all tongue-in-cheek, there was a deeper truth underlying them. Her father was always closed off to her. She never knew what he was thinking or feeling, and so she used a childlike sense of storytelling logic to make sense of him and his slow decline.

Visually, Fayolle employs a deadpan style reminiscent of Gabrielle Bell. The top-notch production values of NYRC are in evidence with the full album format, good paper, and richness of color. Instead of standard word balloons, the comic is narrated by captions told from Fayolle's point of view, written in cursive script. This is an important detail, because this is very much Fayolle's narrative, not her father's, and cursive makes this feel like a personal diary. Fayolle layers the story with multiple interpretations of events, and sometimes those accounts work in concert and sometimes they are contradictory. Infantilization is a running theme throughout the book, and Fayolle's magical storybook approach reflects her own self-infantilization in response to this ongoing trauma. It's all part of what makes reading The Tenderness of Stones such an overwhelming experience: it's a diary, it's a fairy tale, it's a family trauma, it's a child trying to make sense of a confusing world, it's an adult coming to terms with the death of her father.

The simplicity of the plot and even the childlike quality of the narration allow Fayolle to use complicated techniques to solve visual storytelling problems. The second chapter, in particular, is one long visual tour-de-force. There is an extended meditation on the idea that Fayolle's father had become a child again, much to her annoyance: "He had entered a time machine, and he had not taken me with him." Of course, the reality is that her father had deteriorated to the point of being unable to feed himself, dress, or even walk. Fayolle depicts this as though he is an infant, lying in a crib with a mobile above him or being cuddled in a rocking chair. Her formerly icy father now demands a kiss on the forehead before he goes to sleep and needs the door open as he goes to sleep. Throughout this transformation, and throughout the book, Fayolle measures her own identity against his. If she was now older than him, how could he be her father? Who was she now?

Furthermore, this changes her relationship with her mother. She describes her as a big woman whose body always provided security, and she depicts her as bigger than the panel can contain, as she and her adult brother both disappear under her skirts, feeling safe. She suspects that her father had always wanted this kind of mothering, which led him to become a child. However, Fayolle turns it around as an act of kindness on his part, as he did it to distract her mother from noticing that she and her brother were growing up and leaving for new lives. Fayolle depicts herself and her brother with suitcases, floating away from their mother, but the siblings return when they realize their father is too fragile to leave behind.

This is also the moment where Fayolle realizes her new goal: of deciphering the mystery of her father, of wanting to "meet" him at last. She depicts her father as being a silhouette that they slap up images of him on, desperately trying to figure him out and "see" him and hope that he will let himself be seen. This kicks off an inspired series of pages where she has to act as his mouth--literally taking the lips off of her own face and putting them on his so he can talk to his friends. Then she and her brother have to lend him their hands, their legs, and more, in a brilliant 8 x 8 grid that slowly and painfully gets across the difficulty and frequent ennui involved in this level of caretaking. On another page, also with an 8 x 8 grid featuring a different displaced body part in each panel, Fayolle cartoons herself pushing aside panels and tearing a number of them down in an effort to find her leg. The only instance of word balloons in the comic is the next segment, where she and her family start talking for her father, pasting up word balloons of their own design. She admits to changing some of his words before putting them in the word balloon, making him kinder and more loving than he normally would be. It's an intense push-and-pull, where she feels her own personhood in pieces but perceives that she's also altering his agency. It's an almost self-destructive kind of empathy, as she begins to feel his pains and mimics his movements on the page.

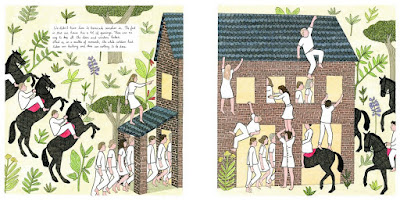

There are many other inspired sequences, including likening the presence of home health/hospice personnel to that of an invasion of the men in white. Of note, many of the dreaded, judgmental men in white are women, but Fayolle conflates all authority as being male, due in part to the influence of her father as this remote, frightening authority figure. Conversely, her mother is a comforting and nurturing figure, and because the women wearing white are neither, they are all referred to as men. What creates tension in the book is a series of these reactions based on childlike, binary logic. If my father needs care like a child, he must have chosen to become a child. If he demands constant care and needs to be the center of attention, he must consider himself to be a king. If he's still hard to know, it's because he's lying about his illness and is sneaking out at night to drink with the fellow lost souls in the local bar.

One of the most beautiful and heartbreaking sequences is at the beginning of chapter three, where Fayolle discusses how she hopes the illness will erode away her father's rough edges like the sea gently smooths over the rough edges of boulders. She writes, "My father was a boulder that I longed to cling to without being wounded. That I longed to shelter beneath without feeling threatened." Instead, as she depicts with beautiful simplicity on a series of splash pages, he becomes even more jagged and "you could still cut your fingers and hurt yourself if you held him too close."

Holding too close and being unable to let go to one's parents in various capacities and with various consequences are also running themes throughout the book. This is finally resolved in the fourth and final chapter, as the men in white decreed that he was dying. The image of invisible, cancerous cells falling from the sky like meteorites herald several pages that all have a single caption: "Dad is going to die." On each page, Fayolle chooses a different visual metaphor for his exit and his family's assistance with it: closing a curtain, packing a suitcase, making him disappear like a magic trick, and levitating off a bed. Fayolle steps outside the narrative for a moment to reveal that she had been in the middle of drawing this book when she learned he was going to die, which made her feel as though she had caused it somehow by drawing his diseased lung. She resents this ending being imposed on her: "I could have come up with a much better finale." This is a moment where she reveals just how dark her sense of humor is, playing around with this naive binary. It's clearly her coping mechanism.

In the end, that humor is abandoned as she depicts her family and herself preparing her dad for one last performance. It's all framed in the language of acting and pumping him and saying he had what it took, that he had been rehearsing for years. The final images are both surreal and exquisitely and painfully beautiful. The spotlight on his last performance remains, with flowers being thrown on stage in celebration of his life — a twist on flowers being sent to the bereft when someone dies. His family is sitting on a bench as they watch the performance, with Fayolle applauding. In a book full of dense backgrounds, this is a page with just a few images and an almost overwhelming use of negative space. The funeral is depicted as a crowd of people smoking cigarettes as his giant body lay outstretched. The smoke looks like stone and also like his diseased lung, which I imagine is no coincidence. The smoke grows thicker and obscures his body. Everyone goes their own way, and the final page sees his body disappear.

The Tenderness Of Stones deals with sickness, end-of-life issues, family bereavement, and caretaking issues with a powerful sense of honesty and authenticity. Too often, narratives about the dead and dying try to smooth over the reality of how we relate to them in real life. Using a clever series of visual metaphors and deliberately making her narrative tone naive allows Fayolle to really "spill some ink" and get at her feelings while still being sensitive to her father's and family's plight. Every page is a marvel of composition. The torrent of visual metaphors brings to mind Tom Hart's Rosalie Lightning, which is about the death of his young daughter. It's as though the layer after layer of metaphors is like Fayolle wrapping herself in blankets for comfort or bandages for healing. At the same time, the clarity of storytelling is remarkably sharp, as she stacks metaphors in some instances and elides them in others. The Tenderness Of Stones is a remarkable achievement whose power in depicting the personal pain of one person and her family resonates for anyone who has ever experienced a loss or been a caretaker.

----------------------------------------------

Rob Clough has written about comics for Cicada, the Comics Journal, Sequential, tcj.com,

sequart.com, Savant, Foxing Quarterly, Studygroup Magazine, as well as for his own blog, High-Low (highlowcomics.blogspot.com).

No comments:

Post a Comment