“I

had a contempt for the uses of modern natural philosophy. It was very

different, when the masters of the science sought immortality and

power; such views, although futile, were grand; but now the scene was

changed. The ambition of the enquirer seemed to limit itself to the

annihilation of those vision on which my interest in science was

chiefly founded. I was required to exchange chimeras of boundless

grandeur for realities of little worth.”

– Mary Shelly, Frankenstein

“For

I consider that the sufferings of this present time are not worthy to

be compared with the glory that is to be revealed to us.”

– Romans 8:18

“Life

boils down to brutality. It's fucked. Life is brutal and fucked up.”

– Noah Van Sciver, Saint

Cole

Living

ain't easy sometimes. Misery, mourning, heartbreak, and suffering

continue to engulf the world despite our technological advances,

oftentimes because of them. The darkness of sorrow is the constant

shadow cast in the bright light of joy. It's thick. It blankets. It's

universal.

There's

this compulsion to utter some sort of statement like, “Ah, life...”

and weasel the self into the comfortable confines of the community of

despondency – that warm, liquid space we tend to float in when it

all gets too much, you know, to keep on keeping on. Because, yeah,

life can be fucking brutal sometimes.

Have

you been reading about the spate of abandoned children being found in

fecal smeared houses lately? Or those homeless people being doused in

gasoline and set aflame? Have you heard of the massacres in Nigeria?

Have you been following the waves of horror that passes itself off

nightly as news?

Fuck.

It's incredible what we do to each other. The pain that people bring

to the lives of others is seemingly unending.

Then,

of course, there's the pain we put upon ourselves, the sharpened

sticks we poke into our own eyes out of guilt or shame or some sad

dysmorphia. When you slam your head against the red brick walls, the

blood that gushes covers you completely. When you spend two years of

your life carefully planning on how to end it, your pain is whole, it

is who you are.

And

even though you keep turning your head, you always end up facing

something.

It's

pretty fucking amazing how many of us actually make it through.

Noah

Van Sciver's new book from Fantagraphics, Saint

Cole, has got me

thinking about my relationship with misery. It's also got me thinking

about the obligations of the artist to his or her art, and, maybe

more importantly, to the audience.

Because

Saint Cole is part of

the long tradition of the balladry of brutality. It sings the song of

the sink hole caused by a life lived in response to expectations it

could never fulfill. It's the chant you hear in the places people

gather to drown out their sorrows, it echoes in the alley behind the

neighbor's house whom you've never met, it rings in your own head

from time to time, that is, if you are sensitive to it.

See,

I had a former student call me the other day and say, “Elkin, why

didn't you tell me it was going to be like this?” “Like what?”

I asked innocently. “Like life...” he replied at 28 years of age,

up to his eyes in student debt, working at a job he hates for people

he hates even more, licking the wounds of a failed marriage,

questioning what he's still doing playing this game.

What

answer could I have given him?

Yeah,

brother, life is hard. Obligations. Expectations. We're fed a crock

of shit so often that it starts to taste like ambrosia, and it

suffuses even our dreams.

We

do it to ourselves all the time. We curl up our fists in response and

end up only punching ourselves in the neck over and over again. And

we reach out, because we've only got each other after all, to our

family, our friends, our lovers to save us from self-harm. And yet

even that, sometimes, ain't enough.

Sometimes

the expectations and aspirations of our family, our friends, our

lovers adds to or transmutes our own and the weight of that shit can

be measured with truck scales.

So

it is with Noah Van Sciver's Saint

Cole.

Saint

Cole follows the story

of the everyman Joe, saddled with a live-in girlfriend and an

unplanned and unwanted newborn baby boy. It's a story of the lower

echelon of society, the ever growing mass of those of us living

paycheck to paycheck constantly slipping down the ladder we have been

teased to climb, trying to hold on to what we have while the top

keeps telescoping to the heavens and the lows are just as low if not

getting lower.

When

you get beaten down over and over again and that light at the end of

the tunnel dims daily like it's powered by a seven-year-old Duracell,

despondency becomes the constant voice-over actor narrating every

aspect of your life. In Saint

Cole, that's where we

find Joe. And, like so many others who are caged, cribbed, and

confined by the jail cell of poor choices and worse economic

prospects, he turns it up to turn it down.

It's

nothing new. We've seen this story of self-destruction in the

protagonists of other works of fiction of this type. From Hubert

Selby, Jr.'s Last Exit

to Brooklyn to Darren

Aronofsky's take on Selby's Requiem

for a Dream, from the

prose of Charles Bukowski to Figgis's adaptation of John O'Brien's

Leaving Las Vegas,

we see individuals make the decision to numb themselves from the

confusion and the stress and the self-loathing infusing their lives

in a way that is, sadly, almost inevitable. It's hubristic in its

way, the choice to escape, and sometimes it becomes the final act,

sometimes it becomes something else, but regardless of its end, the

journey itself is brutal.

Of

Saint Cole,

Van Sciver said, “Sure it's brutal, but in my own experience it's

not unrealistic. I know these guys. You have to work harder for less

today. And when your life is like that, just a grind for nothing,

you'll turn to chemicals to dull it. And you'll make rash decisions.

Sorry to rant, but I get so frustrated with how badly everyone is

fucked in this era.”

And

that frustration is palpable in this book. Saint

Cole is a downhill

slope of unleashed grievance, unrelenting and unremitting in its

pace. As a reader you catch your ski on a rut at the top of the run

and tumble end-over-end gaining momentum as your body darkens with

new bruises and blood starts to run from all the wounds re-opened in

your fall leaving you searching for a bag for your teeth. And just

when you think you're almost to the bottom, there are still new deep

black holes in which to fall.

Yeah,

it's brutal.

Brutal.

I

keep coming back to that word. I'm stuck with it. Saint

Cole is brutal.

But

to what end is this barrage? What purpose does it serve as a work of

art other than as an opportunity for the artist to unload? Why does

Saint Cole

bore into my consciousness, prompt me to put aside so many other

responsibilities to write all these words about it? Why does it make

me want to share it with everyone I know?

Is

it that “transformative power of art” – that purging of pity

and fear that Aristotle was so keen on? Is it that somehow by going

through this with Van Sciver we come out the other side a better

person?

But

really, there's little that's redemptive in this book.

Maybe

Saint Cole

functions as the viscous wallow instead – the comfort of “you're

not alone” that makes this book such a personal experience for me?

Questions....

I

guess I'm brought back to my earlier rumination, about the

obligations of the artist to his or her art, and, maybe more

importantly, to the audience.

By

creating a work like Saint

Cole, does Van Sciver

don the hospital whites of well-trained nurse who's come to our room

to help us with our pain? Is he the cardigan-wearing, pipe-smoking,

belly-rubbing therapist practicing counseling with some tough love

techniques? Or is he a cop in full riot gear swinging his baton with

impunity at our heads as we fall to the street, tight in a fetal

position.

What

is the role of the artist in this situation? Does he have a

responsibility to his audience? Or does the act of creation,

especially one that is this purgative in nature, operate in a moral

vacuum?

If

a work of art beats the living shit out of you, is that the

responsibility of the artist or is it the albatross of audience. When

we carry our reactions to confrontational creative acts chained

around our neck can we still point our finger at the creator?

I'd

like to think that in a perfect world, an artist would be allowed to

create unfettered by any sort of moral compass. That the act of

creation alone is a sacred thing, and that, once created, the art

exists in its entirety, a thing of beauty insofar as it is an act of

imagination. As it holds neither good nor ill in itself, the power is

not in the piece but in our experience with it. When things go south,

it's because of our apperception and all that that entails.

Doesn't

that make it our responsibility then? Maybe we shouldn't hold the

artist accountable at all for what they make us feel or do or say in

reaction to their creation.

Then

again... I began this review, or whatever this is, with a quote from

Mary Shelley's Frankenstein...

I

offer no answers, only more questions. But a work like Saint

Cole demands this sort

of debate insofar as it punctuates as it punches, illuminates as it

beclouds.

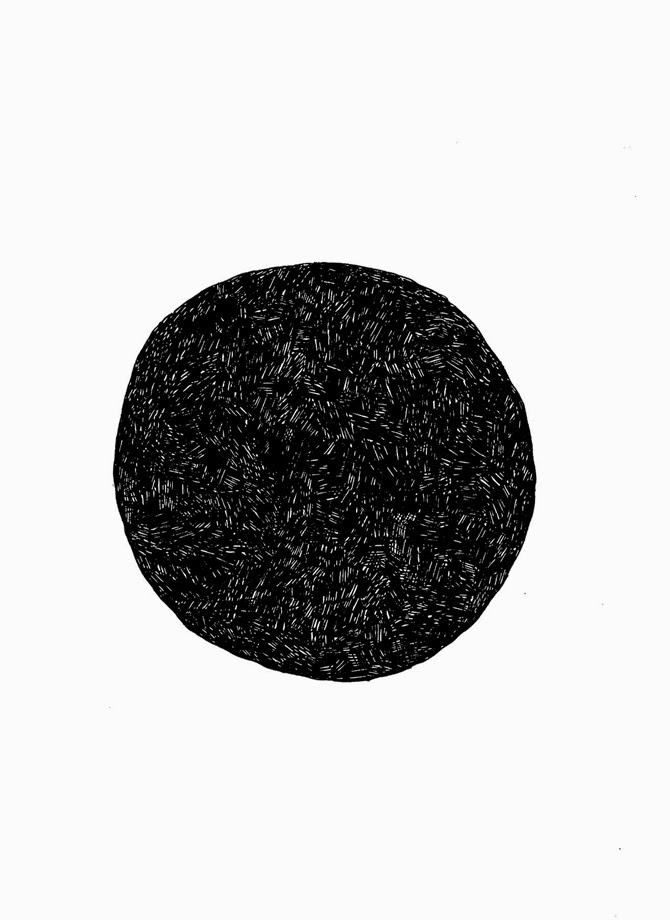

Saint

Cole begins with a

black hole centered on a white page. On the next page a text box

overlaps the hole and asks, “How

did I let things get so out of hand?”

The final page of the book, after everything that happens within,

returns to that same black hole. Darkness is the framing device for a

brutally unyielding story of a man who systematically smashes gaping

wounds into his own life with an industrial-sized sledgehammer. From

the sickly colored cover to the too-tight binding of the book itself,

everything about this work forces you to confront some ugly truths.

And

somehow I know this has value. For some reason I cannot shake Saint

Cole from my mind. I

want to shove it into the hands of everyone I know, though I worry,

of course, what it will trigger in them.

But

then again, is that my responsibility?

Saint

Cole can be purchased from Fantagraphics

No comments:

Post a Comment