Similarly, themes of liberation and possibility are prevalent in the work of cartoonist Whit Taylor. Taylor, a black cartoonist and health educator, frequently engages with issues of race and identity. In “Finding Your Roots,” a webcomic published by The Nib, Taylor explores race and identity through the hairstyle choices of black women. Taylor centers her comic on her experience transitioning from chemically straightened hair to learning how to embrace her hair’s natural texture. She has also collaborated with fellow cartoonist Chris Kindred on the nonfiction comic “African-Americans Are More Likely to Distrust the Medical System. Blame the Tuskegee Experiment.” Published by The Nib on February 26, 2018, this comic presents the history of the Tuskegee Experiment, a clinical study conducted between 1932 and 1972 by the U.S. Public Health Service where black men were infected with syphilis without their knowledge. Kindred and Taylor outline the study and its aftermath, emphasizing it’s unethical nature and lasting impact on the black community.

Taylor is very aware of how race and representation factor into her life and art. In a 2015 interview with Artworks Blog, she stated, “In my work, I explore issues of identity frequently. Being a black woman, issues of race and gender are things that I find myself coming back to because they have and continue to shape who I am and how I perceive the world.”

Using varying degrees of representation, Taylor strategically makes blackness absent and present, engaging with what scholar Deborah Whaley refers to as an “affective progression of blackness” - embedding and layering images to create meaning. This is significant because mainstream media culture still predominantly presents whiteness as the default. Characters are usually thought of as white unless described otherwise.

In her 2016 book Wallpaper, Taylor does not directly code the protagonist as black. Though told in a confessional, almost diary-like style, Wallpaper is not an explicitly autobiographical work. However, the unnamed protagonist does share some similarities with her creator. For example, Taylor is also from New Jersey and has a brother. However, this omission should not be dismissed as an oversight. Taylor’s past work indicates that she is obviously well-versed in racial politics. Watermelon...And Other Things That Make Me Uncomfortable As a Black Person (2011) is an autobiographical work that directly addresses and challenges stereotypes Taylor and other black people have experienced. Wallpaper, though, might seem like a departure in both format and content.

Taylor’s Wallpaper is a meditative, conceptual comic that uses patterns and abstraction for narrative starting points. Wallpaper is notable for its particularly intimate presentation; it is small even by the standards of a minicomic. The cover of the comic depicts a pink and green pattern that is bordered by a striped, repeated delicate floral motif. This unapologetically decorative, feminine cover combined with the small format of the comic makes you feel like you have stumbled upon something secret and precious.

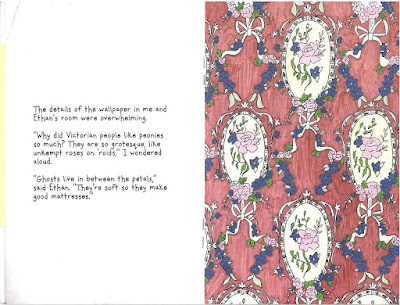

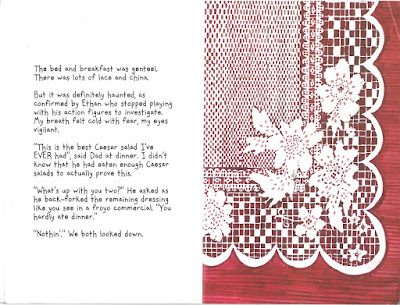

Beyond its small, intimate format, Wallpaper breaks a lot of rules and common expectations of cartooning. It has no panels. Words and images are never presented on the same page. Rather, the left spread contains the narrative text and the right contains a full-bleed drawing of a significant pattern or texture. In Wallpaper, these everyday patterns are used as starting points for the protagonist’s musings. This narrative has the effect of contemplative remembrances, evoking a strong sense of nostalgia in the reader.

Taylor has used unconventional compositional strategies in other comics. For instance, Taylor’s comic “Alternatives to Avocado Toast for 2018” offers wry commentary on how we receive information from the news media. A creative interpretation on trends and the major events of 2017, this comic is arranged vertically with pieces of toast functioning as panels. By putting all of these ideas on toast, Taylor employs an absurdist sense of humor that emphasizes the strangeness of living in contemporary times. In this comic, reports on the use of fidget spinners, handheld devices meant to help people focus, are juxtaposed with stories on climate change. By putting all of these events and trends on toast, it appears to flatten them out and effectively starts to equalize them. Taylor also titles one toast “Escapism Toast.” This toast has a unicorn horn and a mermaid tail, linking these trends to nostalgia and the idea that millennials are turning to imagery from their childhood to provide comfort in an increasingly uncertain, chaotic world.

Wallpaper, on the other hand, focuses on personal rather than collective nostalgia. The first pattern that the comic displays depicts white flowers with greenery against a brown background, representing the wallpaper in the kitchen. The narration on the facing page explains that the protagonist’s mother removed much of the house’s patterns, which were decorative choices by the previous owner. Subsequent patterns are derived from other pieces of the house - tile floors, examples of linoleum, and carpet. However, not every drawing is something that the protagonist physically encountered. One pattern depicts the lickable wallpaper from the film Willy Wonka and the Chocolate Factory. Taylor’s presentation results in flattening them out. By presenting them side by side, Taylor suggests that these fragments all seem to run together for the protagonist, with something remembered from a movie given equal weight to a “real” experience.

Wallpaper progresses with the protagonist continuing to examine the patterns that surround her. We learn more about her family, including a visit to her grandmother’s house and a family vacation to Cape May. As Wallpaper progresses, it becomes apparent that the protagonist is documenting patterns that are disappearing from the house. There is a pervasive sense of loss throughout the piece; it is apparent that things are changing beyond home renovations. Her grandmother moves to an assisted living facility and is later hospitalized.

First published in 1977, A Pattern Language: Towns, Buildings, Construction delineates structural patterns which are viewed as timeless entities. Written by Christopher Alexander, Sara Ishikawa, and Murray Silverstein of the Center for Environmental Structure of Berkeley, California, A Pattern Language attempts to put forth elegant solutions to problems regarding architecture, building, and community livability. It argues that, when considered together, these patterns form a sort of language for building and planning structures. The book itself is organized in a consistent format with a picture illustrating the pattern followed by a paragraph description. While operating on a much smaller scale, Taylor also begins to create her own structural patterns that become language, organizing her comic in a way that more closely resembles fragmented memories. Like A Pattern Language, Taylor uses a consistent format throughout the comic. With the rigidity of this, Wallpaper becomes a microcosm that encapsulates the elliptical nature of difficult memories. Particularly traumatic memories may be virtually impossible to articulate.

Wallpaper uses significant sensory memory, particularly descriptions of taste, to great effect. For instance, when the protagonist recalls dreaming about the edible wallpaper, she also mentions eating a Fruit Roll-Up for breakfast. Later, she describes the walls of the newly repainted den as being the color of Hershey’s chocolate bars and describes accidentally smearing some on a copy of Pride and Prejudice. In Wallpaper, the sweetness of these junk food treats contrast with the more somber mood of the narrative, giving them a cloying rather than indulgent connotation. When the family later goes out for pizza after seeing the grandmother in the hospital, it’s not an entirely unexpected that the protagonist is sick on the car ride back.

Wallpaper concludes with the floral wallpaper in the kitchen getting replaced with beige paint. The protagonist has a strong reaction to this, getting upset with her mother and storming out. The last pattern in the comic is a scrap of wallpaper. The narration reveals that this scrap is actually from a dollhouse. The protagonist explains that she found the dollhouse and fixes it with help from her mom. This dollhouse wallpaper fragment is a fitting ending to a comic done on such a small scale.

Just as A Pattern Language illustrates how simple structures can become components of complex networks, Wallpaper demonstrates how small moments and unanswered questions can have a powerful emotional resonance. Reading the protagonist as a black woman makes sense not only because of Taylor’s own racial identity, it also provides greater resonance as to why the comic is structured the way it is. Taylor does not depict any bodies, letting patterns and the words of the protagonist tell the entire story, creating a rhythm for the dissonance of trauma to reverberate against. Additionally, the black female body is not the focus here. We cannot scrutinize how she chose to depict the protagonist or if she resembles Taylor. Instead, we are given a story which subtly suggests that whiteness is not the default as it delicately limns the struggles of adolescence.

---------------------------------------------------------------------------

No comments:

Post a Comment