KILGORE QUARTERLY #7

Edited by Dan Stafford

Featuring works by Summer Pierre, Tim Lane, Joseph Remnant, Sam Spina, and Leslie Stein

Here’s something that you probably already know: putting together anthologies is a tricky business. It usually takes a certain level of editorial intent in order for a collection to hang together on its own. As far as Kilgore Quarterly #7 goes, though, editor Dan Stafford says this one “focuses on longer works from artists who have orphaned stories. Some of these appeared elsewhere, have gone out of print, and need to be read by more people, some are from forthcoming works, and some just needed a home.” Throwing together something palatable with this sort of junk-drawer editorial construct strikes me as akin to the meals I make at the end of the week using all the leftovers in the fridge. Sometimes it tastes disgusting, sometimes transcendent. You just don’t know what you’re going to get when you throw it all in the pot.

Amazingly, though, Kilgore Quarterly #7 tastes great.

In the end, the disparate voices and styles complement each other by bringing out thoughts and themes that stand out through their juxtaposition far greater than they would have by themselves. Though separate and contained, each piece is magnified by its relationship within the whole. Through what may be happenstance, this anthology ends up being thematically sound -- an exploration of the relationship between art and the artist.

Reading Kilgore Quarterly #7 makes me think that it would benefit by the subtitle: The Art of The Self.

The collection opens with Summer Pierre’s “Dappled Light”, a five-page, thickly inked rumination on the connection between “sitcoms from the 1950’s and 1960’s” and the author’s creative output. Pierre reflects on her past, spending “hours after school drawing to old TV shows” and the escapism that activity provided, an exercise that transported her not necessarily out of time but out of place. A jarring two-panel sequence halfway through “Dappled Light” indicates a certain level of abuse Pierre suffered as a child. This abuse provides the impetus for the connection Pierre feels for these long past TV shows, “a place filled with dappled light -- uncluttered by secrets or rage.” The final horizontal panel of the artist as a young girl curled up on a couch emits the feeling of comfort inherent in escapism. The correlation between the acts of her watching those old shows and of her creating art demonstrates a sense of purpose behind the two endeavors. Here, escapism is at the core of creating the self. Pierre is, in effect, stating clearly that her art is what allowed her to define the person she longed to be.

The next piece in Kilgore Quarterly #7 is “Steve McQueen Has Vanished” by Tim Lane. Drawn in straightforward, naturalistic style, Lane’s use of light and dark elements, plus his choices of perspective and tight close-ups, give the piece a vaguely noir sensibility. Ostensibly, the narrative revolves around a stranger showing up at a roadside motel. The stranger may or may not be the actor Steve McQueen who, according to news reports, has disappeared from public view -- perhaps due to a feud with Paul Newman regarding billing in the film Towering Inferno. Where narrative ends, theme begins, as Lane becomes more introspective regarding the nature of identity, exploring how everything we do, especially creative acts, defines how the world sees us, and how that self is as much a creation as the act itself. Where the true self lies is somewhere altogether different, a place of solitude, reflection, and contemplation. In Lane’s piece, art is a mask the artist wears in public, a persona created by the audience who have projected their own desires and needs onto its face. For the artist, that mask is either something to hide behind or be suffocated by. In the end, Lane’s story becomes more about the narrator than the characters it describes. In that, “McQueen” takes the universal and localizes it to the experience of a stand-in for ourselves.

Would I have read “Steve McQueen Has Vanished” along these lines had it not been for Summer Pierre’s piece prior to it? I don’t think so. Such is the power of putting these pieces together.

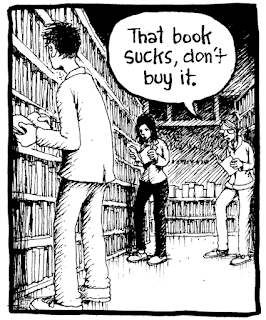

Likewise, Joseph Remnant’s “I Told You So” continues the framing theme of the art of the self. Remnant’s propensity to fill his panels with small diagonal lines belies the influence artists like Robert Crumb have on his work, but it also adds a certain dingy foreboding to his cartooning, as if filth and darkness are constantly threatening to engulf everything. This is another story about understanding a person through the work they create. To be honest, it’s my favorite piece in Killgore Quarterly #7, and it’s heartbreakingly sweet, the kind of comic where you end up smiling a teary-eyed grin at in the end, though the process to getting there is a painful journey to walk. Remnant is able to turn the sad-sack upside-down and unpack its heart. There’s every reason not to root for the protagonist in this piece. After all, he’s a moody, mopey, privileged white boy whose actions, though well-intentioned, smack of, at best, social awkwardness. And yet….

And yet in “I Told You So” Remnant exposes that one’s true self can be found in their art, as long as it speaks to the truth of the heart. If art is pushed out because of some obligatory grasp at what others have expressed is true, then it smacks false and reveals nothing but a void within. When it speaks of the self, though, it is revelatory, worthy of encapsulating that which is the real “you”.

Sam Spina comments further on this idea with his contribution to Kilgore Quarterly #7, “K. Trout Makes His Move”, which wraps itself in an absurd metatextual bind. This comic begins with a down-on-his-luck fish who uses his name, which also happens to be Sam Spina, to get laid. It then pulls back to the “real” Sam Spina who is incredibly pleased for having created “another perfect comic” in a coffee shop, where he is summarily beaten for being a “lanky little freak”. At the end, a fish which had been living in human Spina’s knit-hat comments, “Wow! Your comics just get better and better!” Here the relationship between the artist and his art is bundled into a self-awareness that nobody outside of himself can conceptualize. Art is a lie that serves to bolster the self, to give it power and meaning in a world that is chaotic and draining. Spina’s comic is only of value to himself, empowering him to a moment where the true self is given voice and agency. Though the human Spina is physically repulsed of this idea through the agency of others, the fish in his hat, the idea of self that Spina still grabs hold of, continues to be unswayed. Whatever humor it is intended to convey and/or contains, “K. Trout Makes His Move” is a complex bit of business.

Rounding out Kilgore Quarterly #7 is Leslie Stein’s “The Desk”. In “The Desk”, Stein features her semi-autobiographical character, Larrybear, from her Eye Of The Majestic Creature series. Here, a young Larry builds a desk in the doorway of her room using oversized fake bricks. As her family members walk by, she says, “Hello! Larry’s room! How can I help you?” -- though neither her mother nor her sibling pay her any mind. While this is, on the surface, a simple childhood reminiscence of “playing adult”, there’s still that undercurrent of how artists use their art to define themselves.

There’s a lot to process in “The Desk”. The image of a child using bricks to seal up half of the entrance to their bedroom in order to become something more than they are is the stuff that post-Freudian analysts dream of. The fact that her family ignores her assumed identity, this “false self” that Larry has created through an act of imagination, also speaks volumes as to Stein’s own sense of herself. Larry eventually has to pee. Because of this physical need, she has to break through the wall she has created with her artistry, clearly demarking the line between the self as a corporeal thing and the self as a conceived thing. The body as form must break through the barrier of art in order to satisfy its needs, showing its predominance in the cartesian duality that plagues us all. “The Desk” ends with Larrybear cleaning up her bricks and focuses on a shattered picture frame that holds a portrait of herself. The line between who she is and who she wants to be is clear. It is only through an act of sheer artistic endeavor that she will ever become actualized as her desired self.

Again, Kilgore Quarterly #7 would benefit by a subtitle: The Art of The Self.

All my interpretations of each piece are only brought to the fore through its interaction with the pieces that preceded it. This is the mark of a coherent anthology. Dan Stafford has collected all these “orphans” and has given them a home in Kilgore Quarterly #7. They become a family by the proximity they share. These leftovers only become a truly harmonious meal when they stirred together in the same pot, and I, for one, have become more aware of myself for having tasted this dish.

No comments:

Post a Comment