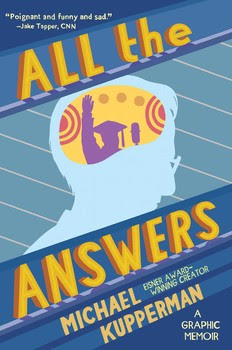

Michael Kupperman is best known for his wildly absurd and deadpan humor comics featuring characters like Snake ‘n Bacon, Pagus, and the duo of Mark Twain and Albert Einstein. There is an intense, labored quality to his art that acts in direct contrast to its light silliness; as you read about Rabid District Attorney, the reader is almost overwhelmed by the dense cross-hatching, heavy use of shadow, decorative effects that come straight from some unidentifiable “old-timey” influence and deliberately stiff character design. References to pop culture are often hopelessly outdated or mutated beyond recognition, like a whole round of Quincy references, Roger Daltry looking to shag some birds but only being offered actual birds to have sex with, and Pablo Picasso threatening to cut things into “leetle cubes”. Kupperman’s whole aesthetic looks to an imaginary past in an effort to disorient the reader and make them feel like they should be understanding nonsensical references.

At the age of six, Joel Kupperman became a regular on a competitive radio trivia program for children called The Quiz Kids. In All the Answers, Michael puts the era in context: child prodigies were a kind of lottery ticket for their lucky parents during this era, as they received a great deal of attention from the press and public. The bubbly and cute Joel became an instant sensation thanks to his ability to compute math problems. He received stacks of fan mail. Famous athletes and entertainers wanted to meet him and shower him with gifts. Yet, it was his mother who was the engine behind all of this, pushing Joel hard even after the experience was no longer any fun for the child. Joel and the other kids were also important for the war effort, urging people to buy war bonds. Joel revealed that he felt certain that one reason he was pushed so hard, in particular, was as a way of fighting anti-Semitism, becoming a sort of Model Jew that all Americans could admire. The show's producer, George Cowan, was Jewish and in charge of a great deal of government propaganda. He saw World War II as possibly an extinction event for Jews and fought it anyway. A meeting requested by industrialist and noted anti-Semite Henry Ford with Joel was a particular highlight of this effort to get the wider public to think of Jews as Americans, first and foremost. Seeing a young Jewish boy support the war effort with the power of his American brain was exactly what the producers wanted, and the fact that Joel was so personable made their job that much easier.

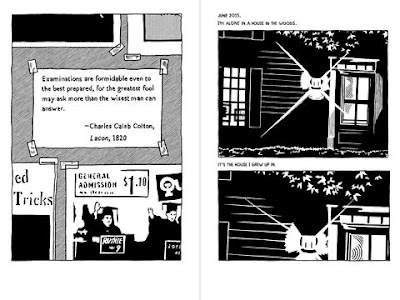

The problem was that eventually, Joel stopped being young and cute, but his mother and the producers still kept him on the show—even when it transitioned to television. As there was no national cause to tie to it anymore, kids started to hate the very thought of Joel Kupperman, as he was often held up as an exemplar of behavior by parents that they failed to live up to. Michael seems to think that while all of that was unpleasant, the event that truly traumatized Joel was going on a quiz show after college in an effort to make real money (he earned a pittance as a Quiz Kid), only to get caught up in the TV quiz show scandal of the 1950s. Michael notes that after that event, Joel disappeared from public life and became a successful philosophy professor, living out in the Connecticut woods. The problem, as Michael notes, was that his father had never truly confronted the trauma from his past, and the result was Joel’s cold and detached parenting style.

The impetus for this book was Joel freely recalling Abbott and Costello giving him a dog when he was a kid, prompting Michael to interview him about it. It was at this point, though, that Fate intervened in a cruel manner --Joel was diagnosed with dementia -- which meant Michael’s project had a ticking clock. It was another bitter irony that just when his father was ready to start talking about his experiences, his mind started to fade. It seems that the book was written for Michael himself as much as it was for anyone, as a way of confronting his own feelings growing up in an angry, distant household and how it wound up encouraging any number of destructive behaviors on his own part. If Joel couldn’t come to terms with the past, perhaps Michael could. And if the whole exercise sounds selfish and self-indulgent, Michael might be the first to agree with you. Even after it was done, he felt a mixture of pride and dread putting it out in the world, as he’s noted in several tweets.

Either intentionally or by good fortune, Kupperman’s art in the book wound up perfectly matching its distant, detached emotional tenor. The book was carefully designed to tie in elements on a thematic level, as each chapter leads off with an image of a bulletin board filled with old articles and a quote by a famous person that related to Joel Kupperman in some way (Philip Roth and J.D. Salinger both made mention of Joel in their fiction). Michael was likely inspired in that regard by a series of scrapbooks that preserved every detail of Joel’s fame (kept by Joel’s mother, of course), he knew he had hit the motherlode. They were hidden deep in his father's personal library. This is true in terms of the facts of the story, but at the same time, it also inspired the visual motifs of the book. This book’s panel-to-panel transitions and character design are deliberately stiff—as though they, too, were part of a scrapbook. Michael’s own self-caricature has beady eyes and a blank expression that shocks the reader a bit when emotion clearly comes over it. On the other hand, the way he draws Joel looks closer to photo-reference, as though his relationship with his father is mediated by the image of what he once was. At the same time, conversations between Joel and Michael have a zip-a-tone background, breaking up negative space with a technique that’s pure comics artifice.

This is a story that’s told in a mostly chronological, straightforward manner, yet its implications and motivations are complex, even to the author. Michael went into the book thinking that his father’s career as a prodigy was a traumatic experience, and his research bore that out. However, the story wasn’t quite as clear-cut as that. The book is about memory and its relationship to trauma, first and foremost. Uncovering the scrapbooks revealed that when Joel was a little kid, being on Quiz Kids was fun. It was an adventure. Everyone was nice to him, and he was (as Orson Welles noted!) entirely unaffected by it all. The difficulty came when he started getting older, particularly with regard to executive functioning. When other people tell you what to do all the time and you are rewarded for your compliance, creating and maintaining one’s own agency can be difficult. Joel stayed on the show because that’s what people wanted him to do, even if he had grown tired of it as a teen. It never occurred to him to just quit and leave the country in order to avoid the kind of abuse he endured on campus from his peers. There’s one harrowing scene where a bunch of guys accost him, yank off his clothes, throw garbage on him, etc, as he all the while tells them that he’s not reacting and he’s in control.

As noted earlier, however, it was Joel going on a quiz show just out of college that really did him in. Shows like the $64,000 Question, when they got to a certain point, were rigged in favor of the contestant as a way to please audiences. When this was discovered, it was a huge scandal and everyone connected to these shows, including Joel, was immediately considered suspect. Joel himself did not cheat, as Michael details. The shows were very cunning in how they did this; in Joel’s case, another contestant invited him out for a cup of coffee. Unbeknownst to Joel, this contestant was a confederate of the show who was told to casually bring up select bits of information in conversation. In this particular case, it was famous parts of operas. When Joel was given the question on TV, he froze because he immediately realized what had happened. He knew the answer on his own and chose to answer it, but he then immediately walked away from the show, sickened that he hadn’t walked away earlier. Michael notes that it wasn’t an accident that Joel’s concentration as a philosophy professor was in ethics. In the process of creating this new life and moving into the woods, he had walled off all of the good memories he had had as well as the traumatic ones. As a result, he had no connection to his childhood, but still retained that sense of thinking that something was only important if someone told him that it was.

There is a heartbreaking sequence at the end of the book when Michael finally confronts Joel about being such a distant father. It’s bookended with an early sequence where young Michael (already suspecting the truth) asks his father if he loves him. Joel’s response was “some of the time”, a response that was cruel but not in an intentional manner; indeed, he was simply being honest when he regarded the question. As Michael writes, “He erased everything, but that left him with nothing to share with me.” The sequence at the end is triggered by Michael asking his father why he didn’t tutor him the way his own dad had. Joel responded that he thought Michael was smart and would figure it out on his own…and it didn’t occur to him that he should construct a relationship with his son. No one told him to do this, so he didn’t do it. This may sound absurd on its face, but anyone who has experienced trauma will immediately understand.

As someone who experienced childhood trauma myself, I relate to that sense of detachment, erasure, and survival, as well as that sense of feeling adrift as a child who didn’t have parents to teach me a lot of things. Early childhood trauma with my parents divorcing a few years later and then my mother’s death as a pre-teen, combined in such a way that certain emotions were no longer allowed, like grief; I didn’t actually cry about my mother dying until over twenty years later. One way or another, those feelings and that pain come back eventually. As outlined in All the Answers, Joel essentially sacrificed his relationship with Michael (who speaks only for himself, not his mother or younger sibling) because he refused to confront that pain. Ignoring it in the way he did stunted his emotional development and intelligence. He became a stereotypical absent-minded professor: brilliant in his own field, but often helpless and neglectful in his everyday life.

A running theme in the book is the question of just what intelligence is. Joel didn’t think he was all that special; he had a great memory, a facility for math, and a way with words. However, he noted that when he took a test that measured spatial relationships, he struggled. To be sure, his emotional intelligence was broken, and he was unwilling to repair it. Doing so would have required professional help, something that ironically simply didn’t occur to him. He didn’t even know what he didn’t know. Michael lets slip in the course of the narrative that he’s writing this book in order to understand himself, especially since he went through a difficult childhood and teen years where he badly needed a role model who just wasn’t there. While Michael keeps the majority of the focus on his father and his story, he occasionally reveals anecdotes like coming home from school one day and telling his father that he had been expelled (Joel’s reaction: “Mmm.”), and, upon hearing this, Michael went out and got arrested for shoplifting. He doesn’t discuss this event any further, but it was clearly a desperate attempt at drawing any kind of reaction from his father, as well as the act of a boy who was desperate because he felt lost and didn’t know what he was doing.

Early in the All the Answers, Kupperman discussed a period in his 30s where he felt like a total failure and actually cried during dinner with his parents. Their reaction was to pretend it didn’t happen. Michael then met someone, got married, and had a son. This book is as much about his son as it is about his father or himself because Michael is trying to figure out how to be the kind of father his son needs. He understands that children absorb everything from their parents, even as they develop their own agency. In my own life, I can see some of the things that I struggled with in terms of executive functioning in my daughter, only my daughter is getting therapy that’s helped her life immeasurably. Michael’s bond with his son is powerful, even as he notes that he’s already learned how to be a difficult artist from him. At the same time, his question at the end of the book, “Does {writing this book} make me a good son, or a bad one?” is also a referendum on being a father. He really doesn’t know if he’s a good son or not because he has no model of what being a good father is like. Like his own father, he was forced into a position of figuring things out for himself while trying to survive.

All The Answers isn’t just about the somewhat vague concept of fatherhood. It is very specifically about child-rearing and the ways in which a parent can mold and manipulate a child. In a real sense, Joel Kupperman was manufactured to be the most famous child prodigy in America. He was told what to read, where to go, what to do. He was brilliant in some ways, average in other ways, and painfully naïve and poorly taught when it came to emotional intelligence. He meant a lot to many people, and there’s no question that using him to help combat anti-Semitism was effective for a while. Michael is careful to note that it certainly wasn’t all bad for his father, but being taught to be obedient had a negative effect on him. And of course, fame brings both well-wishers and those who despise you, and he was not equipped to deal with the latter.

When a child goes through a traumatic childhood thanks in part to the strategies their parents used, the natural reaction when they eventually become a parent is to do everything the opposite of the way their parents did. For good or ill. Michael implies that he all but begged for guidance and direction as a child, but Joel did the opposite of what his parents did: he declined to directly influence or mold his son in any way. In his case, this may not have been a conscious decision, but it’s certainly how it played out. So the questions remain: did Michael Kupperman do right by his father and family in digging up this story? Was it a selfish act on his part? Tacitly, the book is also about Michael’s fear of failing his own son, which is an outcome he won’t know for years, if ever. It is because Michael Kupperman understands and grapples with the notion that these questions don’t have easy answers that makes this a great book. He told his father’s story as authentically as he could, but the fact that he had the guts to admit that this didn’t lead to a magical catharsis doesn’t puncture a hole in the narrative; it simply grounds it in reality.

--------------------------------------------------------------------

sequart.com, Savant, Foxing Quarterly, Studygroup Magazine, as well as for his own blog, High-Low (highlowcomics.blogspot.com).

No comments:

Post a Comment